Authored by: Tracy Sawicki, Executive Director at the Peter & Elizabeth Tower Foundation and Jane Feinberg, Founder and Principal, Full Frame Communications

In 2013, a group of philanthropists gathered together in Beverly, MA for an education roundtable. One of the guest speakers was Jeff Riley, currently the Education Commissioner for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, who was then serving as Superintendent of the Lawrence Public Schools (LPS). More specifically, Riley had been appointed “receiver” of LPS after the state took over the district because of poor student outcomes. The philanthropists wanted to know: “How can we be most helpful to school districts like yours?” His response was swift and clear: “No pretty ponies,” he said. By that he meant that funders might think about checking their favorite school reform models, personal agendas, and dreams of brand building at the door when working with schools. He was encouraging humility—an attribute that can sometimes be in short supply in philanthropic circles.

Our two organizations, New Profit and the Peter & Elizabeth Tower Foundation, took Riley’s directive to heart. Before we share that story, a bit of context about our two organizations is in order.

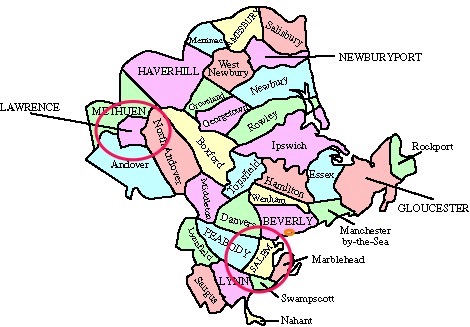

The Peter & Elizabeth Tower Foundation (the Tower Foundation), based in Buffalo, New York, targets its funding to organizations that serve youth with behavioral health challenges, with learning disabilities as a newly established focus area. Most of the Foundation’s work is regional in outlook, with grants given primarily in Western New York (Erie and Niagara counties) and in Eastern Massachusetts (Essex, Barnstable, Dukes, and Nantucket counties). Its impact has been primarily in the programmatic and practice realm.

New Profit is a national nonprofit venture philanthropy organization based in Boston that funds and advises social entrepreneurs toward large-scale, systemic impact. Much of its work is in the field of education and career readiness. One of its signature efforts is Reimagine Learning, which focuses on how to meet the diverse needs of all learners, particularly those who face challenges such learning disabilities, learning and attention issues, trauma, the effects of poverty, or behavioral issues. Reimagine Learning’s work is centered on scaling practices, policies, and networks that advance innovative solutions for the nation’s most vulnerable students.

Given our organizations’ shared interest in better meeting the needs of learners for whom the current system is not a good match, New Profit invited the Tower Foundation to partner on this national effort as a lead funder, despite the Foundation’s traditionally regional focus. The Tower Foundation saw the partnership as an opportunity to understand the educational landscape, but asked that New Profit, through the Reimagine Learning initiative, go beyond its core work of funding social entrepreneurs and create a set of proof points in school districts within the Foundation’s geographic footprint that are rethinking educational approaches to better support diverse learners.

Our first two efforts took place in school districts in Lawrence and Salem, two cities in the extreme northeast corner of Massachusetts, which is part of the Tower Foundation’s catchment area. The basic idea was to field test the hypothesis that schools stand to gain most dramatically when they focus on improving conditions for students who traditionally find learning most difficult in our current one-size-fits-all system. This approach is sometimes known as “targeted universalism.” Angela Glover Blackwell writes compellingly about this concept, calling it the “curb-cut effect,” a reference to the ramps on street corners initially intended to serve Americans with disabilities that quickly demonstrated outsize benefits that accrue to everyone—parents with strollers, for example.

The notion that philanthropy seeks to “field test” innovations within a school system—to come in with a predetermined plan of action—is a problematic one and district leaders have good reason to be skeptical of consultants or social entrepreneurs that wade in with a miraculous cure to what ails their schools. While funders may be able to offer grant dollars, they often lack local context—and access to money is no guarantee of significant, positive change. Mark Zuckerberg’s 2010 investment of $100 million in Newark, NJ public schools is just the most well-known case in point. In fact, with rare exceptions, third-party offers to pilot or test a particular curriculum or intervention are simply unrealistic given the monumental pressure facing school districts on a daily basis. Busy teachers and administrators cannot be expected to run learning laboratories for philanthropic foundations, however well-intentioned they may be.

So, in heeding Riley’s call for “no pretty ponies,” we were determined to embrace a more relational and emergent approach to systems change. In the case of the Lawrence Public Schools, we held several meetings with Riley and his team, asking simply: “What are your urgencies?” Our goal was to see if the district’s needs in any way matched New Profit’s competencies; in other words, the intersection of the two would indicate the discovery of a “sweet spot” for joint work.

As it turned out, the Lawrence Public Schools had just received the initial findings of a quantitative study conducted by Harvard University: researchers had concluded that a single intervention—the Acceleration Academies—was a key success factor in the district’s turnaround. The Academies consist of a week of intensive learning during the February and April school vacations, matching exemplary teachers from around the country with struggling students who can benefit most from intensive instruction.

Reflecting on the Harvard study, Riley said that he wanted to better understand the core elements that make the Academies so effective—what we’ve come to call “the secret sauce.” He invited New Profit to investigate its qualitative dimensions—to document and codify the intervention such that the lessons learned could be shared widely, both within and beyond Lawrence. What resulted was a website and multi-media platform (named “The Golden Ticket” after the process by which students are invited to attend the Academies) that includes 30 short videos and a robust “Lessons Learned” section for every altitude of the educational system: state, district, school, and classroom. Perhaps the most exciting development during our time on this project was the creation of a separate 501(c)(3) called the Sontag Prize, which is now bringing Acceleration Academies into other school districts in Massachusetts. While the new organization was not the direct outcome of our work, Riley told us that it was a contributing factor to its creation in that we validated and promoted the strength of the model.

As with Lawrence, we entered the Salem Public Schools by sitting down with Kim Driscoll, the city’s entrepreneurial mayor, and the newly arrived school Superintendent Margarita Ruiz—a Latina educator who had risen through the ranks in the Boston Public Schools. Together, we identified areas of common interest and kept in touch after our initial conversation via email correspondence. A couple of months later, Ruiz called to ask if New Profit would consider facilitating a community-driven strategic planning process in the district—a capacity that was within our wheelhouse and would provide the Tower Foundation a front row seat to systems change work in schools.

New Profit accepted the invitation with enthusiasm and began a yearlong engagement that included more than 60 community meetings, resulting in a strategic plan that was community-developed and unanimously approved by the School Committee. From the start, we were insistent that the plan be theirs, not ours. Thus, throughout the process, we positioned ourselves as back-of-the-room facilitators—scheduling meetings, preparing stakeholders to lead the meetings, researching issue areas, developing talking points, and helping to write the final version of the strategic plan. Only very rarely did we find ourselves at the front of the room. In essence, we opened up for the district a much-needed space for learning and reflection, and by virtue of our presence, we held them accountable to one another. In the daily madness that is the life of a Superintendent and her leadership team, we believe that a trusted outside partner can be critical to keep the momentum going. We codified the experience by creating An Educator’s Guide to Community Engaged Strategic Planning, a web-based platform that both documents the process in which we engaged the district and provides a range of strategies and tools for others to use freely.

In both Salem and Lawrence, our work was not programmatic in nature and, consequently, we did not directly contribute to improving educational outcomes for students with diverse learning needs. In both instances, however, we played a valuable role in elevating or helping to create the structures and systems that support such learners. In the case of Lawrence, we told the story of an effective intervention for struggling students in the hopes that others would learn from it and replicate the model and/or its lessons. In Salem, we co-designed a process for the district and community to jointly shape a vision for the schools and helped shape a district-wide agenda in which the needs of diverse learners were foregrounded.

The critical lesson here is that enduring change requires patience and active listening; it involves being ready and willing to spend significant time and dollars simply tilling the soil. By walking alongside our partners in the school districts, instead of dictating from above, and by trusting their instincts and supporting their agenda, we had the opportunity to learn, to ask questions, and to have a seat at the systems change table. And because our two organizations are proximate to nonprofit organizations that have developed innovative solutions to the problems educators face, we could listen for need and match the district with an appropriate partner or solution. A case in point: early on in our work with Salem, the district recognized its challenges in meeting the social-emotional needs of many of its students; it desired more than a piecemeal plan. City Connects, a member of the New Profit portfolio, is a school-wide model that provides children, youth, and families with access to a vast array of supports, and provides educators a sophisticated, technology-driven data platform for monitoring progress. City Connects is now operating in almost all of the public schools in Salem. Without City Connects, the district could have easily spent a decade building a similar system. Because of New Profit’s role as relationship broker, Salem discovered City Connects and was also one of the first school districts to implement the Acceleration Academies through the Sontag Prize.

Finally, our work in Salem and Lawrence helped establish Reimagine Learning’s credibility in Essex County and has opened up new opportunities to effect change that we would not have earned without the strong relationships we built in the county. Currently, in partnership with the Center for Collaborative Education, we are working with six school districts in Essex County to help school leaders and teachers build capacity in meeting the needs of diverse learners. The educators in the Essex County Learning Community (ECLC) are hungry to expand their repertoire of skills and are ready to align their practices to better reach the students in front of them. We’ve also enlisted eight members of the Reimagine Learning network to provide their deep expertise to the ECLC in the topics that districts have surfaced as their greatest areas of need—whether it’s by teaching at the monthly meetings or offering on-site or remote coaching to the districts. The ECLC experience will culminate in a Showcase of Learning, in which districts will present action plans for meeting the needs of diverse learners. We hope they will build on this work for years to come, with or without our support and involvement.

Effective change in complex systems is an emergent proposition; when you begin, you truly do not know how it will all unfold. We fool ourselves by thinking that we can bring our tonics and elixirs and watch dramatic cures take place. Grantees, for this reason, are often wary of funders, whom they may view as interlopers that offer cure-alls, not practical solutions. Our aspiration is to shift that frame, by offering a profoundly different role for philanthropic partners—more of a humble wellness coach that listens and is present in an honest and organic partnership. Help with the diagnosis certainly, but be less quick to prescribe.