Part 1

[This installment of a two-part series looks at the performance of Tower grants when measured against specific project goals; Part 2 will look at the broader impact of the same grants.]

About every year and half or so, we take a look at the latest cluster of closed grants and assess their aggregate effectiveness and impact.

So once again we ask the question: Are Tower grants effective? This time we looked at 44 grants that closed between May 2018 and December 2019. Since most of our grants are multi-year grants, this actually represents well over 70 years of programming/project time.

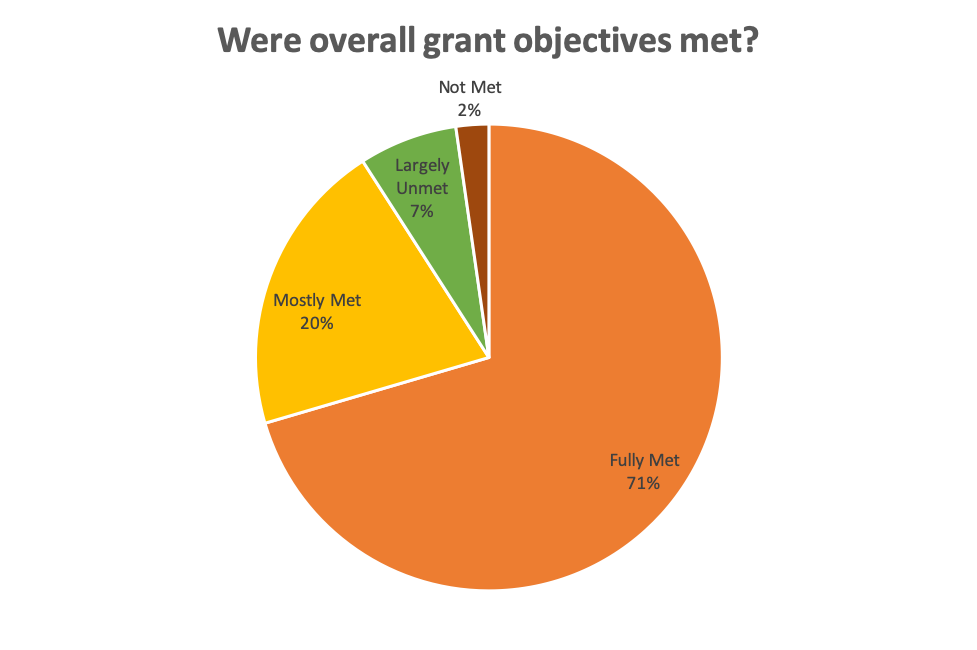

When a program officer closes out a grant they complete an internal assessment form that we call “Lessons Learned.” Drawing on site visits, interim reports, final reports, and the relationships we build with grantees, we respond to this question: Were overall grant objectives met? We looked at the objectives that the grantee had described to us when they applied for funding. The scoring options include “Fully Met, Mostly Met, Largely Unmet, Not Met At All“.

Just to give you an example of what these objectives might look like: an agency may have identified the ability to offer a new intervention to 100 clients annually as a project objective, or to reduce recidivism rates in youth they enroll in programming. When we review final reports from our grantees, we take a look at progress towards these objectives.

It should be said that we fully expect that grants may miss their targets, sometimes widely. Maybe there is more to learn from these projects than from ones that go swimmingly from start to finish. What assumptions were disproven? How did unexpected environmental factors come into play? It is also worth noting that Tower program officers are scoring grants from their own grant portfolios, so this is not a completely unbiased process.

This pie chart shows what we found for the 44 grants that we scored.

What did we see from these 44 recent grants? Ninety-one percent of the grants met their objectives, either in full (71%) or mostly (20%). Nine percent fell fairly short of meeting expectations: largely unmet (7%), not met at all (2%). [This tracks fairly closely with the last time we assessed grant impact (June 2018) when we saw fully met at 64%, mostly met at 30%, largely unmet at 4%, not met at all at 2%]

“Fully met” did enjoy a bit of a jump, from 64% to 71% — and I have a theory about that. This period of grantmaking saw something of a shift, for a number of reasons that I will not go into here, to grant-funded projects of slightly less duration (one or two-year grants becoming more common) and reduced complexity. With this came more modest program goals and grant targets that were easier to hit squarely. A second factor potentially at play is work on the part of the program officers to build relationships with grant partners, to be open to emergent factors that can shift project priorities, and focus more on learning than grant compliance. This can change the way grant success is understood and assessed. There is a third factor too. During this period of evaluation, most program objectives were developed in workshops with Tower program officers – with an emphasis on outcomes that were both reasonable and achievable.

As previously, we looked first at “failure drivers,” the factors/conditions that contributed to grants underperforming. A few critical failure drivers emerged.

- For projects implemented across school districts, buy-in must be secured at the building level and district leaders must support staff actively to reinforce this (cited 2x).

- Delegating work to a young, motivated program staff is fine but they must be supported, particularly when corrective action is required.

- If achieving a clinical diagnosis is critical to a program, fully understand the obstacles to achieving it.

- Program staff turnover is a particular threat to effective evaluation. There should be some shared “ownership” of program data and metrics.

- Partners that are brought on without some kind of track record bring greater risk to the project.

- Engage evaluators early in the process and test for alignment of evaluation with goals that the grant partner really cares about.

- In the face of regulatory and process change, don’t be too rigid about traditional staff roles.

- Families resisted interacting with a website for mental health supports.

- Development of peer leaders proved more difficult than expected.

- Organizational leaders understandably want to project confidence, but need to be wary of over-promising on program goals (and possibly giving short shrift to the role of program staff in original program design).

- Resist the temptation to assume that recruiting for your program will be easy.

- Consider the impact of unanticipated budget cuts on a specific initiative.

We also wanted to look at what made projects successful. Here are some of the “success drivers” we identified for projects that fully or mostly met objectives.

- Recognize the need to customize curriculum for new populations, new conditions.

- Focus on outreach before attendance numbers lag.

- Capable, consistent project management (cited 3x).

- Take the time to select curriculum, interventions, etc. that are a fit with clinical staff and client base.

- When entertaining strategic alliances, pay attention to your own existing infrastructure, staffing structures, and processes.

- Relationships with foundation staff can help with connections to possible partners.

- Leg-work to establish demand up-front will pay off (cited 2x).

- Test staff for buy-in ahead of time (is there appetite for a particular training? are their potential champions? Existing structures to tap into –like a wellness team?) Particularly important in education settings (cited 3X).

- Develop relationships with local colleges.

- Don’t assume parent buy-in. Work to generate it and recognize that it can take time. (cited 2x).

So what do we do with this information? We know we want to capture the stories (and the learning) that our grantee partnerships tell us. When we work with prospective grantees or review grant proposals, we look for program designs that can harness success drivers. And, from the failure drivers, we know to caution grantees about the common pitfalls in both planning and execution.

In Part 2, we look at the broader impact of our grants. Do they have a pronounced, positive effect on the target population served, the strength of the organization, or the field as a whole?

[Part 2: What about the broader impact of our grants?]